Surgical alternatives to radical neck dissection (classic), when indicated and oncological feasible, include the following:

Modified radical neck dissection type I Modified radical neck dissection type II Modified radical neck dissection type III Selective Neck Dissection(The reader is refered to the Indications section to understand the rationale for the several neck dissection options.)

Other associated surgeries include the following:

Laryngectomy Composite resection GlossectomyTracheotomy (The patient may need a tracheotomy for control of the airway, particularly when radical neck dissection is associated with a composite resection. Also, consider a tracheotomy in any patient undergoing surgery that may lead to airway compromise.)

Dermal graft (Although optional, a dermal graft has been used over the bifurcation of the carotid artery when a pharyngotomy surgery is combined with a radical neck dissection or radiation therapy. The levator scapulae muscle can be transposed forward over the carotid system for the same reason.)

The following items should be noted on the patient's record before performing surgery:

Physical examination findings, including those of a head and neck examinationMedical history (eg, allergies to medications; hypertension, diabetes, cardiopulmonary disease, and other chronic illnesses; previous surgeries, radiation therapy)

Medical clearance and recommendations All test results, including biopsy and fine-needle aspiration results Informed consent with risks and complications having been fully discussed with the patient Summarized problem and treatment plan, including alternative plansOther preoperative details include the following:

Evaluate the airway and dentition of the patient. Evaluate the ability of the patient to open his or her mouth adequately for intubation. If the patient has a tracheotomy, evaluate the airway and status of the tracheotomy. The patient should remain on nothing by mouth (NPO) status after midnight.Instruct the patient to take the usual medications up to midnight the night before the surgical procedure.

Note premedication order on record. Void on call to the operating room.Preoperative antibiotics are required if the procedure involves going through the neck into the upper aerodigestive tract.

Standard instrumentation used in the radical neck dissection can be found in the Iowa Head and Neck Protocols. Surgeo preferences vary widely.

In the last 5 years, small and medium surgical clips for hemostasis and vessel ligation have been introduced, in addition to the harmonic scalpel. [69]

If the airway is obstructed (see Preoperative details), the tracheotomy is preferably done with the patient under local anesthesia. An obstructing neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract can bleed easily at intubation, producing a sudden, total airway obstruction in an already compromised airway. Prevention and planning are mandatory.

In a difficult but not obstructed airway, the anesthetist may perform an awake intubation with the assistance of a flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy to accomplish a nasotracheal intubation. As an alternative, DL + VL (Direct Laryngoscopy and Video Laryngoscopy) intubation devices can also be used to achieve proper endotracheal intubation in these patients. The intubation can be obtained by direct visualization, or by video imaging in the screen or a combination of both. There are several DL/VL devices available on the market today.

Airway compromise or marginal compromise in patients with head and neck cancer is not uncommon. Therefore, good communication and understanding between the surgeon and the anesthetist is essential.

A urologic catheter is not needed during radical neck dissection. If the surgery is performed with other procedures that are more complex and prolonged, insert a catheter for better control of urine output.

Place the patient in the supine position with a shoulder roll extending the neck. Elevate the upper half of the operating table to a 30° angle. The patient's neck and upper chest are prepared and draped in a sterile fashion for the proposed surgery. Use staples or sutures to delineate the field.

Several incisions are designed and used by various surgeons. If a radical neck dissection is to be performed alone, the hockey stick incision is generally preferred. The neck incision changes depending on the location of the primary tumor and whether one or both sides of the neck are operated on. In general, the incisions are designed to avoid trifurcation over the carotid artery and to avoid narrow flaps.

Although not our preference, a single transverse incision in the neck has been used to perform a modified radical neck dissection. [66, 67]

Mark the skin incision with methylene blue or a surgical marking pen. Some authors infiltrate the skin incision with 10 mL of lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine to minimize bleeding. The author's institution does not infiltrate the skin incision.

Make scratch marks to assist in the alignment of the flaps at the end of the operation.

Make the skin incision through the platysma and elevate the flap in the subplatysmal plane as seen in the image below. Traction with the surgeon's fingers and countertraction by the assistant with 2 double skin hooks are helpful in this maneuver. After raising the superior lateral aspect of the flap, leave the greater auricular nerve and external jugular vein on the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Elevate the posterior flap toward the trapezius muscle.

--> The skin incision is made through the platysma, and the flap is elevated in the subplatysmal plane. In the superior lateral aspect of the flap, leaving the greater auricular nerve and the external jugular vein on the sternocleidomastoid muscle is important. The posterior flap is elevated toward the trapezius muscle.

Identify and preserve the marginal mandibular nerve at the superior aspect of the flap. This nerve passes deep to the platysma muscle, often dropping inferiorly to 2 cm below the body of the mandible. This nerve passes within the fascia of the submandibular gland. A simple way to protect this nerve is to divide the anterior facial vein at the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and to dissect the superior flap deep to this vein.

Some surgeons proceed from below to above, and others do the opposite. The author's institution usually proceeds first with the zone I dissection and then from inferior to superior.

Remove submental fatty tissue with Bovie electrocautery and displace it inferiorly. Retract the mylohyoid muscle anteriorly, exposing the submandibular ganglion, lingual nerve, and submandibular duct. Ligate the facial artery above the digastric muscle. Cut and ligate the submandibular duct. Remove the submandibular nodes and the submandibular gland and displace them inferiorly. The dissection continues posteriorly, exposing the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles and transecting the tail of the parotid gland.

Expose the sternocleidomastoid muscle and incise it above the clavicle with Bovie electrocautery as seen in the image below.

--> The sternocleidomastoid muscle is exposed and incised above the clavicle with Bovie electrocautery.

Identify the anterior and posterior belly of the omohyoid with transection of the omohyoid posteriorly. Note that the omohyoid crosses the internal jugular vein laterally as seen in the image below.

--> The anterior and posterior belly of the omohyoid is identified. Note that the omohyoid crosses the internal jugular vein laterally.

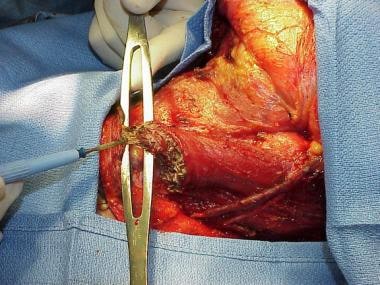

Identify the internal jugular vein and vagus nerve in the lower aspect of the neck before ligation of the internal jugular vein. Pass a 2-0 silk suture around the vein and tie it as depicted in the image below.

--> The internal jugular vein is identified in the lower aspect of the neck, and a 2-0 silk suture is then passed around the vein and tied.

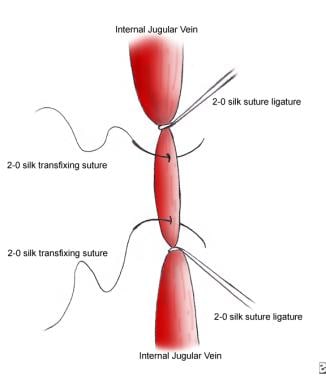

Using 2-0 silk, place a distal suture ligature while the vein is still intact. Place 2 similar sutures cephalic and transect the vein as seen in the image below.

--> 2-0 silk sutures and suture ligatures are placed as shown.

Further identify the carotid artery and the vagus nerve. Open the supraclavicular fatty tissue using blunt dissection, either with a finger or hemostat, with identification of the phrenic nerve and brachial plexus as seen in the image below.

--> The supraclavicular fatty tissue is opened using blunt dissection with identification of the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve appears as a white cord down the midline of the anterior scalenus muscle. The internal jugular vein has been ligated and transected. The carotid artery is seen on the top of the image. The transverse cervical artery is seen at the bottom of the image.

Once the brachial plexus is visualized, blunt dissection with the surgeon's finger permits clamping of the fibrofatty tissue with a large clamp. The spinal accessory nerve is sacrificed in the radical neck dissection; therefore, no identification of the nerve is required.

Pull up Dissect from inferior to superior as depicted in the image below.

--> The submental fatty tissue, the submandibular nodes, and the submandibular gland have been removed and displaced inferiorly together with the specimen.

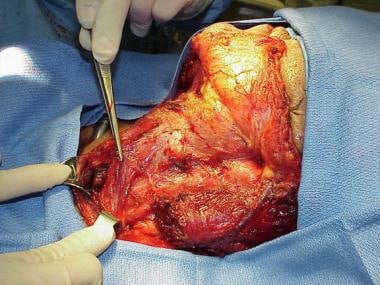

Continue the dissection along the anterior border of the trapezius. Preserve the phrenic nerve and brachial plexus. Follow the cervical nerve branches and section them high on the specimen. Separate the surgical specimen from the carotid and vagus, proceeding superiorly, with identification of the hypoglossal nerve. Preserve the superior thyroid artery and superior laryngeal nerve and carefully ligate the ranine veins. Cut the sternocleidomastoid muscle superiorly in the same manner as described above. The division is made high, and the surgeon is just lateral to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Identify the internal jugular vein superiorly, medial to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Dissect and ligate in the fashion described above and also depicted in images below.

Within the last 5 years, the authors have introduced the use of the harmonic scalpel [22] in the execution of the radical neck dissection. Its progressive use has displaced, in part, most other conventional intraoperative techniques used for providing hemostasis (eg, clamping, tying, electrocauterization). The authors have also found that using this tool shortens intraoperative time and diminishes bleeding. See the images below.

--> The internal jugular vein is identified superiorly, medial to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The ligation of the internal jugular vein at this point is performed with a 2-0 silk suture and a distal suture ligature.

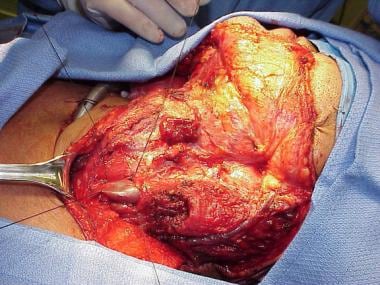

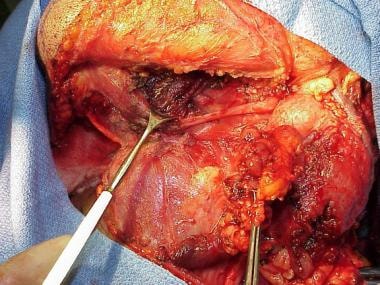

--> Final aspect of the surgical wound after removal of the operative specimen.

Minimally invasive surgery with the assistance of endoscopic and robotic instrumentation [23, 24, 25] has been tried in head and neck cancer management, including neck dissection for cervical metastatic disease. The viability of neck dissection has been demonstrated using this armamentarium; however, its oncological application in the management of neck metastasis versus the classic open approach remains to be seen. Further assessment and follow-up are needed prior to its application in routine clinical practice. [26, 68]

See the list below:

38720, Radical Neck Dissection (Cervical Lymphadenectomy, complete) 38720 with modifier 50, Radical Neck Dissection for bilateral procedureSee the list below:

Internal landmark: This landmark is the scalenus fascia muscle. (There is no need to dissect behind the carotid artery.)

See the list below:

Marginal mandibular nerve: Identify and preserve the nerve by direct visualization, electrical stimulation or by identification of the anterior facial vein and elevate below its plane.

Internal jugular vein: Identify and ligate the Internal jugular vein, superiorly and inferiorly, as described in the intraoperative details.

Phrenic nerve: Identify and preserve the phrenic nerve above the anterior scalene muscle and medial to the transverse cervical artery.

Irrigate with isotonic sodium chloride solution. Maintain hemostasis. Insert drains (0.125-in Hemovac or Jackson-Pratt); usually, use 2 for each side of the neck. Close the wounds in layers with 3-0 Vicryl through the platysmal flaps and staples or 4-0 nylon for the skin.

No compressive dressing is used for bilateral neck dissections. Some surgeons use a compression dressing for unilateral neck dissection.

When preparing the pathology specimen, plastic plates with life-size drawings of the different areas of the neck are recommended for orientation. The unfixed specimen is placed as it appears in the patient and brought to the pathology department from the operating room. The type of dissection performed is written clearly on the requisition slip.

Advanced deeply attached neck metastasis, recurrence after radiation or chemoradiation, and metastatic neck abscess pose several technical challenges for the head and neck surgeon in the salvage operation. Frequently, the neck has acquired a hard boardlike consistency or a frozen-neck appearance, which makes the dissection and identification of anatomical structures difficult. In these cases, the authors proceed with radical neck dissection in a nonstandardized fashion—from the known to the unknown, from superficial to deep, and from the easy areas to the more difficult areas. Along the way, the authors identify major vascular and nervous structures and take small dissection steps.

Most of the time, the Bovie electrocautery unit is used with the assistance of the gentle spreading action of an intermediate hemostat. With this technique, the metastatic mass is dissected en bloc in a circular fashion (superiorly, inferiorly, laterally, medially [in no particular order]). The authors Identify key anatomical structures such as the anterior and posterior belly of the digastric muscle; the omohyoid muscle; the facial artery; the vagus, hypoglossal, and phrenic nerves; the internal jugular vein; and the carotid artery until the entire specimen is dissected, except in its deepest plane.

In cases of advanced metastasis, recurrence after chemoradiation, or metastatic neck abscess, the internal jugular vein is not usually problematic because, in most cases, this vein is already nonfunctional, either because of invasion or compression-blockage by the mass, which occurs superiorly, inferiorly, or both. The vein is usually smaller, and ligation or transfixation-ligation is feasible. However, careful dissection is required over the carotid artery, particularly if infiltration by the tumor is present. Therefore, the deep plane of the mass over the carotid artery is addressed last, as further assessment is needed to determine involvement or invasion prior to consideration of different surgical options.

If the spinal accessory nerve is preserved, identify the nerve in the posterior triangle and dissect it from the anterior border of the trapezius to the sternocleidomastoid muscle until it is free. If the internal jugular vein is preserved, identify it posteriorly after the cervical nerve branches are divided. Then, peel the vein from the surrounding tissue until it is free. Perform this in the same fashion in selective neck dissection. If the sternocleidomastoid is to be preserved, the procedure is performed by peeling the fascia from the muscle. This is done in the same fashion in selective neck dissection.

See the list below:

Maintain nothing by mouth status for at least the first 24 hours. If the radical neck dissection has been combined with more extensive surgical procedures, a longer period may be needed.

Maintain head elevation at a 30° angle. Monitor vital signs, intake, and output every 4 hours. Maintain constant humidification, suctioning, and cleansing of the tracheotomy tube. Administer pain medications as needed. Ensure that the Hemovacs or drains are functioning properly.Ensure that drains are maintained on continuous suction until they drain less than 20-25 mL in 24 hours.

Ensure that the drains do not clot.Administer antibiotics for the first 24 hours if the surgery involved opening the neck and the upper aerodigestive tract.

Monitor for fever, bleeding, or hematoma formation in the postoperative period.Avoid atelectasis. Move the patient out of bed the day after surgery with assistance. Encourage deep breathing and early ambulation with assistance.

Monitor for possible fistula if the oral or upper digestive tract was opened, particularly during the third or fourth postoperative day.

Once the suction and drains have been removed, the patient can be discharged from the hospital, usually on the fourth or fifth postoperative day, if the following conditions are met:

Satisfactory healing of the surgical wound No evidence of bleeding or infection Adequate airway and nutrition Hemodynamic stability Adequate family or home care support Initiation of physical therapy to the shoulder before discharge and continuation at homeIf another surgical procedure was performed in addition to radical neck dissection, the discharge day varies.

See the list below:

Call the patient at home after discharge to check on progress. Arrange for the patient to return to clinic (RTC) in 7-10 days. Check the pathology report for complete or incomplete resection and free margins. Check the pathology status of the neck. Evaluate for further consultations and adjunctive treatment as needed.Remove sutures or clips at 7-14 days; however, when radiation therapy has been administered, they should remain in place for at least 10 days after the operation.

Continue with shoulder physical therapy if necessary.Follow-up care is mandatory to check for recurrent tumor or development of a second primary tumor. Therefore, the patient should be seen every month for the first year, particularly if no primary lesion was initially found. Continue follow-up care every 2-4 months for up to 5 years. After this interval, the patient may be seen yearly. Advise the patient to call for an immediate appointment if the patient's condition suddenly changes.

For excellent patient education resources, see eMedicineHealth's patient education article Cancer of the Mouth and Throat.

Radical neck dissection has been a well-established procedure for surgical removal of neck node cancer for almost a century. A radical neck dissection alone has low morbidity and mortality rates; however, the association of composite resection and ablation of a large surface of mucosal area adjacent to the neck markedly increases the rate of complications.

Previous radiation therapy is another factor associated with a high complication rate. Other factors, such as poor general health, chronic malnutrition, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, advanced age, and systemic illness, also increase the percentage of complications.

Severe blood loss is an uncommon complication for an experienced head and neck surgeon. The average blood loss in the realization of a radical neck dissection is 200 mL or less; it varies slightly according to the surgical technique and among surgeons. With careful attention to anatomy, hemostasis with the electrocautery unit or bipolar forceps and use of clamps and suture ligation have allowed an almost bloodless neck operation. The recent addition of the harmonic scalpel to the armamentarium has allowed a shortening of the operative time and diminished bleeding.

Major vessel trauma, laceration, tear, or transection (internal jugular vein, junction of internal jugular vein and subclavian and/or carotid arteries) is presently a rare occurrence. Immediately repair injury to the carotid artery during surgery.

Consultation with a vascular surgeon may be useful depending on the intraoperative findings. A small tear or laceration requires primary closure with a 6-0 continuous vascular suture. Other types of injuries may require ligation or reconstruction. Injury to the internal jugular vein at the upper or lower ends may be a serious problem.

If the lower end of the jugular vein bleeds excessively, pressure is the first aid, followed by adequate visualization and suctioning until the stump is identified, dissected, and ligated properly. Occasional uncontrollable bleeding requires the assistance of a thoracic surgeon to enter the superior mediastinum.

If the upper end of the vein bleeds and the stump has retracted into the temporal bone, packing the jugular foramen with large pieces of Surgicel, plicating with the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, or both are sufficient to solve the problem.

Carotid sinus reflux

Hypotension caused by carotid sinus reflux may occur upon dissection around the carotid bifurcation. This may be avoided by careful dissection at the carotid bifurcation without manipulation, injection of 2 mL of local anesthetic into the adventitia at the carotid bifurcation between the internal and external carotid arteries, or both.

Pneumothorax involves a sudden compromise of the respiratory and circulatory system and causes difficult breathing, bronchospasm, and decrease in oxygen saturation. The pressure of the anesthetic bag does not cause normal expansion of the thorax.

This complication is rare today. To minimize the chance of pneumothorax, carefully dissect in the paratracheal area and base of the neck with good hemostasis, adequate visualization, and careful dissection of the tissues close to the apex of lung.

If the pneumothorax is small, close the wound with an airtight seal. Follow-up care with conservative management controls the situation without sequelae. Conversely, a large pleural leak with a tension pneumothorax requires immediate aspiration with a No-14 or No-16 needle in the upper anterior thorax, placement of a chest tube with an underwater drain, or both.

This complication is also rare today. Air embolism can occur when a large vein is inadvertently opened. A large volume of air enters rapidly into the open vein by negative pressure and passes directly into the right atrium, causing a sudden alteration of the central circulation, leading to tamponade of the heart and even death. Clinically, cyanosis, hypotension, and a loud churning noise over the precordial area appear suddenly, and the peripheral pulse disappears.

The treatment of air embolism requires packing or clamping the offending vein immediately and turning the patient onto the left side with the head down. Cardiac arrest may occur, requiring aspiration of the air from the heart, massage, and standard resuscitation procedures. Prevention is best, with careful identification and clamping of the major veins of the neck. Adequate ligations and transfixion sutures are mandatory.

Embolism may occur and lead to stroke. Most patients with cancer are of the age at which arterial cerebrovascular disease is common. Careful handling of the carotid arterial system in the neck with gentle retraction, ligation, and manipulation prevents the dislodgment of arteriosclerotic plaques from the internal carotid system.

The neck area has multiple sensory nerves that are sacrificed during radical neck dissection. Therefore, a loss of sensation occurs in multiple areas, including the neck, posterior occiput, external ear, mandibular region, lateral shoulder, deltoid area, and upper pectoral area. On occasion, the formation of a neuroma at the end of a cut nerve may cause paresthesias and pain.

The ramus mandibularis is preserved in most neck dissections unless it is involved by metastatic disease. The transection of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve produces lower lip weakness. If the tail of the parotid is resected, follow the nerve into the parotid tissue before the removal of this tissue.

The sacrifice of the cervical sympathetic chain produces Horner syndrome, which involves ptosis, anhidrosis, and miosis.

The sacrifice of the spinal accessory nerve, mandatory in the classic radical neck dissection, produces shoulder drop with local pain in the affected area and limitation in the range of motion of the arm and shoulder. Most patients tolerate this disability and improve markedly with physical therapy. In type I modified neck dissection, the spinal accessory nerve is preserved, therefore sparing the consequences of the nerve's sacrifice.

Unilateral resection of the hypoglossal nerve is usually well tolerated without serious sequelae; however, bilateral hypoglossal nerve resection causes a severe disability with serious difficulties in feeding, swallowing, and speaking. On occasion, a feeding gastrostomy tube is recommended for adequate nutrition.

Resection of the lower or middle neck of the vagus nerve, which carries motor and sensory branches to the larynx and pharynx, causes vocal cord paralysis.

Avoid injuring the brachial plexus by properly identifying the anatomic planes. Reapproximate the sectioned brachial plexus with an 8-0 or 9-0 nylon monofilament or silk.

Poor wound healing after radiation or chemoradiation therapy

Patients who have received radiation or chemoradiation therapy before radical neck dissection tend to have increased postoperative complications (eg, wound infection, fistula, flap necrosis, osteoradionecrosis, carotid artery rupture).

Chylous fistula is a complication occasionally produced during dissection of the thoracic duct region. Most chylous fistulas occur on the left side. If it occurs, ligate the thoracic duct.

Reinspect the area before completing the surgery. Ask the anesthesiologist to apply positive pressure to reevaluate if further leaking occurs. A small leak can be identified with the assistance of the microscope. Ligation is mandatory. A suture ligation with a figure 8 using 4-0 silk is usually satisfactory. Hemoclips also have been used when the leakage is clearly visualized.

See the list below:

Chylous fistula: Chylous fistula is evident in the postoperative period in approximately 1-2% of patients who undergo neck dissection procedures. Chyle can be identified by the appearance of a milky clouded fluid in the Hemovac drains. Chyle accumulation under the flap can cause redness and swelling of the flap with induration of the surrounding tissues. The leak, if minimal, is usually controlled by aspiration, pressure dressings, and a low-fat diet. Ligation of the offending thoracic duct is required when the leak is extensive with more than 500 mL of drainage and when conservative management has not led to demonstrated improvement.

Electrolyte disturbances: The most common electrolyte disturbance in the postoperative period is hyponatremia. It is usually dilutional; however, it may be related to the secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Clinically, it can be manifested by mental changes, including depression and hallucinations. Occasionally, hypernatremia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, and hypophosphatemia are also associated with radical neck operations.

Radical neck dissection results include the following:

In a neck with negative histologic findings, the recurrence rate is 3-7%. In a neck with positive histologic findings, the recurrence rate is 20-70%.Extracapsular spread commonly is found in small nodes (25%) and large nodes (75%). The extracapsular spread can decrease survival by half and can decrease the disease-free interval.

Macroscopic extracapsular spread is associated with a recurrence rate of 45%, and microscopic extracapsular spread is associated with a recurrence rate of 25%.

Perineural and perivascular invasion are associated with more aggressive tumor behavior. Involvement of the tumor margins carries a poor prognosis and a high risk of recurrent neck disease.Patients with several involved nodes (≥ 4) have a worse prognosis than those with only one involved node.

Multiple levels of involvement are associated with a recurrence rate of 70%; only one level of involvement is associated with a recurrence rate of 35%.

In general, the characteristics of nodal metastasis that affect the prognosis in radical neck dissection include the following:

Extracapsular spread: This adversely affects the prognosis. The pathologist looks systematically for extracapsular spread, which is commonly encountered. Tumor spread beyond the capsule of a lymph node is the most important prognostic factor related to recurrence in the neck.

Perivascular and perineural invasion: Perineural and perivascular infiltration of the tumor is correlated with the risk of lymph node metastasis in the neck.

Sites of nodal involvement: The prognosis and survival rates are poor when multiple levels of neck nodes are involved. Posterior triangle and contralateral involvement is also an indication of poor prognosis.

Number of nodes: A greater number of involved lymph nodes portends a poorer prognosis. This leads to a higher risk of recurrence and a poorer survival rate.

Node fixation: Fixation is adherence to the surrounding structures. Adherence to the carotid artery or a muscle is an ominous sign. In general, fixation occurs with large masses and portends a poor prognosis.

Involvement of surgical margin: Positive surgical margins are common in advanced tumors and carry a poor prognosis.

Recurrent disease: Recurrent disease after surgical neck dissection is an ominous sign.Degree of differentiation: The risk of cervical metastasis correlates with the grade of tumor differentiation at the primary site. Poorly differentiated tumors are more aggressive and carry a poor prognosis.

Once the neck has metastatic disease, adequate treatment is essential. Preoperatively, no ideal method exists to identify metastatic disease clearly. Therefore, false-positive and false-negative results are common. Adequate treatment for metastatic neck disease has long been surgery, radiation therapy, or both.

In the last decade chemo/radiation therapy without surgery has been added to the armamentarium of treatment methodology for patients with head and neck cancer. This methodology includes treatment of the primary tumor as well as the neck metastasis. Patients who demonstrate persistence neck disease following this nonoperative approach are then being offered surgery in the form of salvage neck dissection.

In general, the management is not standardized and varies between institutions, geographical areas and surgeons. Initially, radical neck dissection was the operation used to control metastatic neck disease and an N0 neck. Now, head and neck surgeons agree that a radical neck dissection is not indicated in the absence of palpable neck metastasis or an N0 neck.

Modified radical neck dissection and selective neck dissection are adequate operations for palpable neck metastasis. The selection of a modified radical versus a selective neck dissection is controversial because the decision to preserve nonlymphatic structures remains an intraoperative surgical decision.

The N0 neck is a controversial subject. Many treatment choices exist, including whether to treat electively or to wait and observe, whether to perform surgery or radiation therapy, whether to operate on one side or both, and whether to use modified radical neck dissection or selective neck dissection. Indications need to be standardized.

Future considerations in the management of neck metastasis include the following:

Develop better techniques for evaluation of neck metastasis. Define and standardize the clinical criteria worldwide for a particular neck dissection. Define and standardize indications for preoperative or postoperative radiation therapy of the neck. Define and standardize indications for chemoradiation, before and after surgery. Define and standardize indications for an N0 neck. Define and standardize indications for an N+ neck.Define and standardize the role of PET/CT in assessment and identification of neck metastasis. [27, 28]

Investigate and analyze the prognostic factors. Continue clinical research in these areas.The skin incision is made through the platysma, and the flap is elevated in the subplatysmal plane. In the superior lateral aspect of the flap, leaving the greater auricular nerve and the external jugular vein on the sternocleidomastoid muscle is important. The posterior flap is elevated toward the trapezius muscle.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is exposed and incised above the clavicle with Bovie electrocautery.The anterior and posterior belly of the omohyoid is identified. Note that the omohyoid crosses the internal jugular vein laterally.

The internal jugular vein is identified in the lower aspect of the neck, and a 2-0 silk suture is then passed around the vein and tied.

2-0 silk sutures and suture ligatures are placed as shown.The supraclavicular fatty tissue is opened using blunt dissection with identification of the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve appears as a white cord down the midline of the anterior scalenus muscle. The internal jugular vein has been ligated and transected. The carotid artery is seen on the top of the image. The transverse cervical artery is seen at the bottom of the image.

The submental fatty tissue, the submandibular nodes, and the submandibular gland have been removed and displaced inferiorly together with the specimen.

The internal jugular vein is identified superiorly, medial to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The ligation of the internal jugular vein at this point is performed with a 2-0 silk suture and a distal suture ligature.

Final aspect of the surgical wound after removal of the operative specimen. Axial contrast-enhanced neck CT showing an extensive mass of the left side of the neck.Patient in supine position and head turned to the right side. Radical Left Neck Dissection completed: The classical radical neck dissection encompasses the lymphatic nodes in levels I-V. View of the surgical wound after removal of the operative monoblock specimen. S = Superior. I = Inferior. M = Medial. L = Lateral. (1) Anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle. (2) Carotid artery and vagus nerve. (3) Anterior cervical nerve root. (4) Phrenic nerve. (5) Brachial plexus. (6) Internal jugular vein, inferior aspect, cut and ligated. (7) Anterior scalene muscle. (8) External jugular vein, inferior aspect, cut and ligated. (9) Hypoglossal nerve. (10) Sternocleidomastoid muscle, superior aspect, cut.